A Canadian study has reignited interest in creating cold fusion, a form of nuclear energy achieved at room temperature.

Cold fusion is heating up again as a hope for an endless supply of energy generation. Cold fusion is a theoretical nuclear reaction occurring at or near room temperature—radically different from conventional fusion, which requires million-degree temperatures.

The idea, if proven, would mean virtually limitless, clean energy, using materials as simple as hydrogen and palladium. But proving that cold fusion even exists has been elusive for more than three decades.

However, University of British Columbia (UBC) researchers have reexamined the possibility of a cold fusion reaction as a radical energy generation form. Will their study in Nature inspire others to explore cold fusion?

Cold Fusion Skepticism

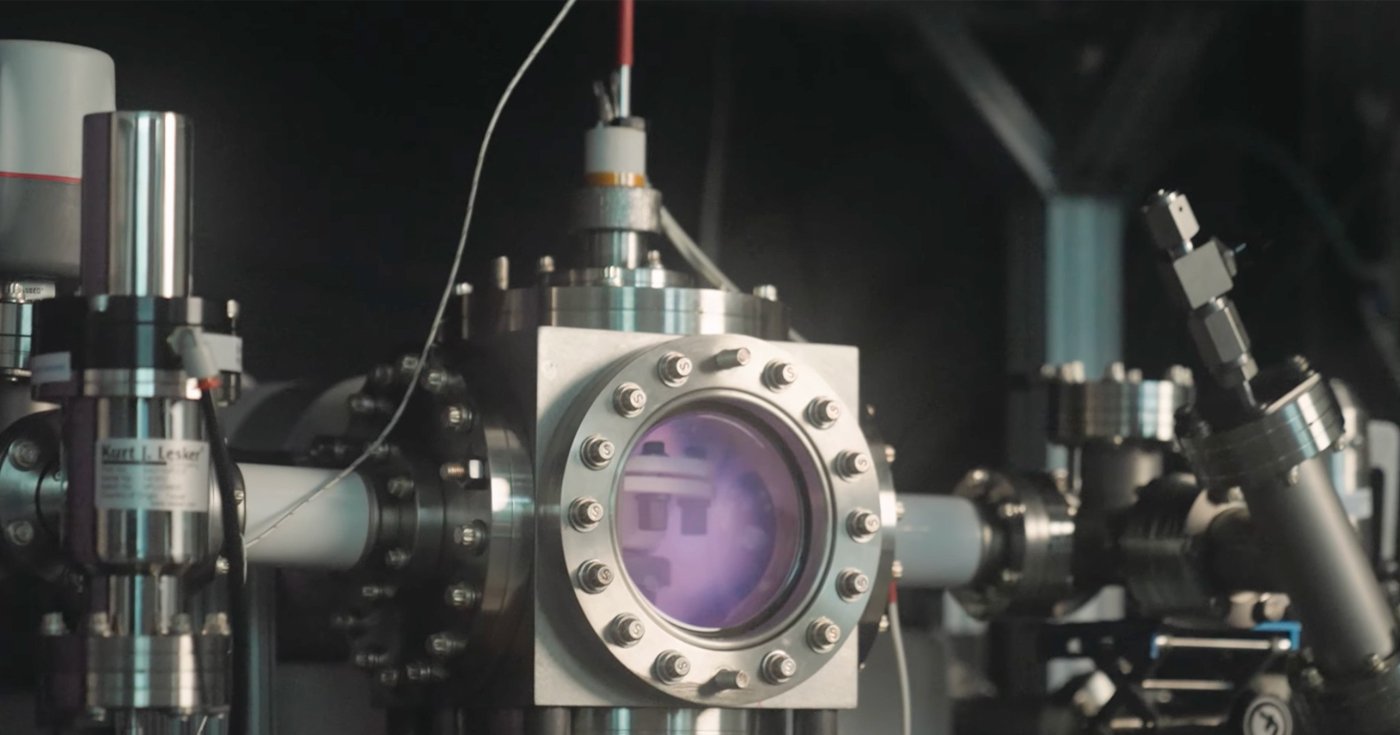

In March 1989, electrochemists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischmann, from the University of Utah, claimed to have produced excess heat during an experiment with heavy water and palladium, far exceeding the energy input. This suggested nuclear fusion, combining hydrogen isotopes (deuterium) to produce helium, neutrons, and energy, was happening at room temperature—a feat previously thought impossible.

Unfortunately, attempts to replicate Pons and Fleischmann’s results failed. Groups at Texas A&M and Georgia Institute of Technology initially reported positive results. Texas A&M saw excess heat, and Georgia Tech announced neutron production. However, both later retracted their claims after discovering instrument flaws (bad wiring and false positives due to detector exposure to heat).

Stanford University reported a small degree of excess heat was formed during their experiments, but standard chemical differences between heavy and light water could explain the result. Further, as Stanford did not measure radiation, peer reviews evaluated its findings as inadequate. It was later found that the researchers’ calorimetry (heat measurement) did not account for uneven mixing, heat loss, or gas evolution, which resulted in misestimating their “excess heat.”

The consensus quickly shifted – most physicists tagged cold fusion as an experimental error rather than a genuine discovery.

Hoax or Hope?

Because most of the scientific community concluded the original claims were due to mistaken measurements, not fraud, the story endured as a cautionary tale rather than deliberate intent. Pons and Fleischmann were reputable scientists; their mistake stemmed from hasty publication and lack of reproducibility, not malice or deception.

Read full article on eepower.com >