Prominent earth scientist urges New Zealand to lead during his recent visit to the New Frontiers summit

“As a scientist I’ve never had so much reason to be nervous; and as a scientist I’ve never had so much reason to be hopeful.”

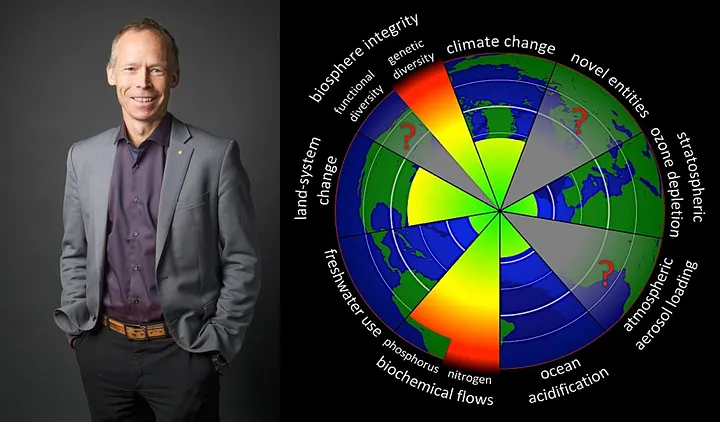

This was the essential message Johan Rockström, one of the world’s leading earth scientists, delivered this past week about climate change and our responses to it during his visit to New Zealand.

He entrusted a particular task to us: agriculture and food production globally present the greatest climate change challenge of all. Their big adverse effects on the ecosystem are compounded by associated impacts through deforestation, agricultural monocultures, biodiversity loss and the declining health of soils and water.

All up agriculture broadly defined is the largest single source of greenhouse gases globally, says Rockström, who founded and leads the Stockholm Resilience Centre. But their technological and economic pathways to sustainability are far less clear than those for energy, transport and the built environment. There are agricultural examples but we need much more innovation and ways to scale them up.

He believes New Zealand has a leading role to play globally in this agricultural transformation. On one hand, agriculture emissions are 49 percent of our total emissions, by far the highest proportion for a developed economy. On the other, our farmers and the scientists and businesses that support them, are among the most innovative in the world.

As an aside on that latter point, agricultural innovation is remarkably slow compared with all other industrial sectors. The average time from innovation to peak deployment of a new piece of agri-tech is 19.2 years here versus 52 years in the US. This insight was delivered recently to a symposium of Our Land and Water, one of our government’s 11 long-term National Science Challenges. Clearly, we have to innovate far faster.

But, Rockström stresses, the window of opportunity to address the totality of climate change is very small. Humankind is still generating a rising volume of emissions. If we are to stand any chance of keeping the rise in global temperatures to under 2 degrees C we have to start bending the curve down by 2020 then accelerate our emission reductions to a rate of about 6–7 percent a year.

While that might seem like a manageable rate, it will actually require transformational shifts in technology across all sectors of the economy. Pathways that are technologically practical and economically viable are increasingly clear in electricity and other sources of power, in transport and industrial processes.

For example, renewable electricity and other forms of energy, after growing by 5.5 per cent a year for the past 15 years, are starting to demonstrate exponential growth. A world free from fossil fuels is possible by 2045, Rockström says.

If, though, humankind can reduce its emissions by 6 to 7 per cent a year, we would halve emissions every decade and achieve near-zero emissions by 2050.

This is the Global Carbon Law Rockström and colleagues are proposing, equivalent to Moore’s Law in computing. It is the latest development of the work of the Stockholm Resilience Centre.

But maintaining that rate of reduction in carbon emissions over the next 30 years will take far more than just a complete switch to clean energy and sustainable agriculture.